Jacques-Louis David, 1818

Love in the Shadow of Duty

In The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis, Jacques-Louis David—known for his heroic Neoclassical style—paints not a battlefield, but a battlefield of hearts. It is a moment suspended between love and longing, farewell and fate.

This tender painting captures a parting between two young souls: Telemachus, son of Odysseus, and Eucharis, a nymph-like companion from the island of Calypso. Their story is drawn from Les Aventures de Télémaque, a novel by Fénelon that reimagines Homer’s epic through a moral and emotional lens.

A Tender Embrace Before the Journey

In the painting, the figures are nestled close, their bodies turned toward each other yet held apart by destiny.

- Telemachus, seated in a flowing blue cloak trimmed with gold, gazes out with gentle sorrow. His bare chest is softly lit, showing strength beneath calm. In one hand, he holds a spear—a sign of the journey and the trials ahead. His other arm is encircled by Eucharis, who leans into him with aching closeness. A white hound peers quietly at the scene, a faithful witness to this wordless goodbye.

- Eucharis, dressed in a rose-colored tunic, rests her head against his shoulder. Her eyes are closed, her grip around him tender but tight, as if trying to hold time in place. A golden quiver on her back and another at Telemachus’s side remind us that both are warriors, though now caught in a gentler, more human conflict.

This is not a kiss, nor a tearful plea—but the quiet, aching stillness of two people who must part despite love.

The Inner Conflict

David’s canvas doesn’t roar. It whispers. The tension is not of armies but of emotion: the struggle between duty and desire, between a calling to something greater and the call of the heart.

Telemachus must continue his quest to find his father, Odysseus. Eucharis must remain behind. Their expressions, their posture, and the very stillness of the scene speak volumes—of love that cannot stay, and of strength that comes with letting go.

David, nearing the end of his own life, poured extraordinary sensitivity into this painting. It’s as if he paused from his grand historic scenes to show us the most intimate heroism of all: saying goodbye to someone you love, and walking the path you must.

The Power of Quiet Emotion

The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis is a painting about love unfulfilled—not in tragedy, but in quiet nobility. It reminds us that farewells are part of every hero’s journey, and that strength is not only found in action, but in restraint.

The figures glow softly against a dark, cave-like background. Their youthful beauty and elegant drapery recall classical sculpture, yet their humanity feels close, tender, and real.

Eternal Themes in a Timeless Image

Jacques-Louis David gives us more than mythology—he gives us a mirror to our own lives. Who hasn’t felt the weight of parting? Who hasn’t had to choose between love and duty, comfort and calling?

In this embrace, we feel both closeness and distance, and in their goodbye, we remember the ache—and the beauty—of love that lingers even when paths divide.

About Artist

Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) was a French painter who became the leading figure of Neoclassicism, a movement that rejected the frivolity of the Rococo and sought to revive the moral and aesthetic values of ancient Greece and Rome. His art was not just beautiful; it was a powerful tool for political and social change. David’s work defined a new style that was severe, intellectual, and deeply political, making him a central figure in the French Revolution and later, the court of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Artistic Style and Legacy

David’s style is characterized by a dramatic shift from the soft, sensual curves of Rococo to the sharp lines and moral clarity of Neoclassicism. His paintings are known for:

- Classical Themes and Heroes: He drew heavily from ancient history and mythology to tell stories of virtue, civic duty, and self-sacrifice.

- Sharp, Defined Lines: He rejected the loose brushwork of the Rococo in favor of crisp, sculptural forms that give his figures a sense of heroic grandeur.

- Moral and Political Messages: His art often served as propaganda, urging viewers to embrace patriotism and civic virtue.

- Controlled Lighting: He used strong, raking light to emphasize form and clarity, avoiding the dramatic tenebrism of the Baroque.

Artwork Profile

Here paintings represent the full range of his career, from his early Neoclassical masterpieces to his later works for Napoleon.

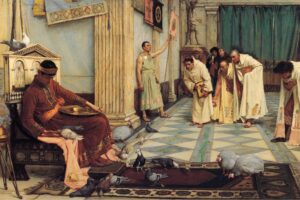

- Belisarius Begging for Alms (1781): An early Neoclassical work that depicts the Roman general Belisarius, unjustly fallen into disgrace, begging for money. It’s a clear moral statement about the cruelty of the state.

- The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons (1789): A powerful and stark depiction of a Roman leader who chose civic duty over personal love. This painting, with its clear composition and somber tone, was seen as a call for revolutionary sacrifice.

- The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis (1782): A more sentimental and intimate work from his early career, it depicts a scene from a classical novel, showing his softer side before his full turn to political subjects.

- The Death of Socrates (1787): One of his most famous masterpieces. It portrays the Greek philosopher Socrates as a moral hero calmly facing death. The painting’s noble composition and stoic emotion made it an icon of Enlightenment ideals.

- The Anger of Achilles (1819): This late painting, from his exile in Brussels, shows David returning to classical subjects with a more refined and emotionally charged style.

- Oath of the Horatii (1784): Arguably his most famous work and a manifesto of Neoclassicism. It depicts three Roman brothers swearing an oath to their father, prioritizing duty to Rome over family. Its stark, geometric composition and powerful moral theme made it an instant sensation.

- Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801): A famous equestrian portrait of Napoleon as a heroic figure. The painting is a work of political propaganda, portraying Napoleon as a dynamic and determined leader.

- The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries (1812): A more intimate portrait of Napoleon, but one that still emphasizes his power and intellectual prowess. It shows the emperor standing in his study late at night, a subtle nod to his tireless work ethic.