A Quiet Ritual of Care

The Milkmaid – Johannes Vermeer, c. 1657–1658 – Genre Painting, Dutch Baroque

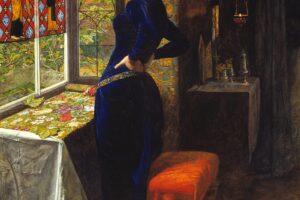

She stands alone in a room bathed in morning light, pouring milk with gentle attention. Painted by Dutch master Johannes Vermeer in the late 1650s, The Milkmaid is one of the most beloved and iconic examples of genre painting—simple, domestic, and full of quiet reverence.

Although Vermeer painted relatively few works in his lifetime, each one is a small world of light, texture, and mystery. In The Milkmaid, he elevates a humble act into something near sacred.

The Scene Before Us

A young maid stands beside a simple table, pouring a steady stream of milk into a clay vessel. Around her, we see coarse bread in a basket, a jug, and small ceramic tiles along the wall. The kitchen is plain, but sunlight spills in from a high leaded window, warming the wall, the maid’s face, and her apron.

Her dress—earthy yellow, faded blue, and soft red—feels worn but honest. The folds of her sleeves are rolled up for work. Her head is slightly bowed, not in submission but in concentration. She is not posing. She is not aware of us. She is simply doing what needs to be done.

And in that simplicity, Vermeer finds beauty.

The Deeper Meaning

Much like his other domestic interiors, Vermeer doesn’t tell a grand story—he lets light, silence, and gesture speak. The milkmaid, often dismissed in history as a servant, is here treated with the same attention a noblewoman might receive in a court portrait. Her work is not background; it is the focus.

There is dignity in labor. There is holiness in care. The act of pouring milk becomes a small ceremony, as if Vermeer is reminding us that even the smallest rituals of life—nourishment, tidiness, routine—are worthy of our full attention.

Note the thick wall, the few rustic objects, the bare space. This is no lavish Dutch interior. And yet, it feels full. Full of presence. Full of warmth. Full of light.

A Moment Caught in Time

The beauty of The Milkmaid lies not in what happens next, but in the stillness of now. This is a moment many would have overlooked—an ordinary chore, an ordinary room. But Vermeer sees more. He sees grace in motion. He paints not just what the eye can see, but what the heart can feel.

Over three centuries later, her presence still speaks to us. She reminds us to slow down, to notice the details, and to honor the hands that prepare our meals, clean our homes, and keep the world turning—quietly, gently, without applause.

About Artist

Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675), a Dutch painter from the city of Delft, is widely regarded as one of the most masterful painters of the Dutch Golden Age. Unlike contemporaries who were prolific and traveled widely, Vermeer lived a relatively quiet life, producing a small but exquisite body of work—only about 36 paintings survive—that has earned him the title “The Sphinx of Delft” due to the mystery surrounding his life and techniques.

Mastery of Light and Atmosphere

Vermeer’s genius lies in his unparalleled ability to capture the subtle effects of light. His paintings are not simply illuminated; they feel as though they are filled with a serene, pearlescent light. He often depicted a single window on the left side of the canvas as the primary light source, creating a soft, diffused glow that gives his interiors a sense of peace and intimacy. This technique, a departure from the dramatic tenebrism of Caravaggio, allows him to meticulously render the textures of objects, the folds of fabric, and the gentle shadows on a person’s face.

Subject and Style

While he began his career with large-scale biblical and mythological scenes, Vermeer is best known for his genre paintings—depictions of everyday domestic life. His subjects are often women absorbed in quiet, contemplative activities: reading a letter, playing a musical instrument, or pouring milk. These seemingly simple moments are imbued with a sense of quiet dignity and psychological depth. His paintings are not overtly narrative; instead, they invite the viewer to contemplate a single, suspended moment in time.

Technical Innovations and “The Camera Obscura”

Vermeer’s extraordinary realism and his signature “circles of confusion”—small, blurred highlights on shiny surfaces—have led many art historians to speculate that he used a camera obscura, a precursor to the modern camera. This device projects an image from an outside scene onto a surface inside a dark room. While he likely did not trace the images directly, the use of such an optical tool would have helped him understand and render the effects of light, perspective, and depth of field with an almost photographic precision.

Notable Works

Vermeer’s small oeuvre includes some of the most beloved paintings in art history:

- Girl with a Pearl Earring: A captivating “tronie” (a study of a face) that, through its striking use of light and the subject’s enigmatic expression, has become one of the most famous paintings in the world.

- The Milkmaid: Celebrated for its remarkable rendering of light and texture, this painting transforms a simple domestic chore into a monument of quiet strength and beauty.

- View of Delft: One of only two surviving landscapes by the artist, this painting is a masterpiece of Dutch Realism, capturing the city’s atmosphere with an incredible sense of scale and detail.

- The Art of Painting: An allegorical work that many consider to be Vermeer’s most significant. It shows a painter at his easel (believed to be Vermeer himself) in the act of creation, a profound statement on the value and importance of art.

Vermeer’s influence has grown immensely since his rediscovery in the 19th century. His meticulous technique, profound sense of stillness, and ability to elevate the mundane to the magnificent continue to captivate audiences worldwide.