Table of Contents

Overview

Painted in 1888 by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912), The Roses of Heliogabalus is a breathtaking Victorian reimagining of ancient Rome’s opulence and cruelty. It depicts the young Roman emperor Heliogabalus reclining at a banquet, watching with calm amusement as his guests are smothered by an avalanche of rose petals poured from above.

Alma-Tadema’s fascination with classical antiquity shines in the luminous detail of marble, mosaic, silken robes, and cascading flowers. Yet beneath the surface beauty lies an unsettling theme: the peril of excess, the fine line between pleasure and destruction.

When first exhibited, the painting stirred fascination and unease, celebrated for its dazzling realism but also criticized for its decadent subject. Today, it is remembered as one of Alma-Tadema’s masterpieces, a perfect marriage of historical reconstruction, aesthetic opulence, and allegorical warning.

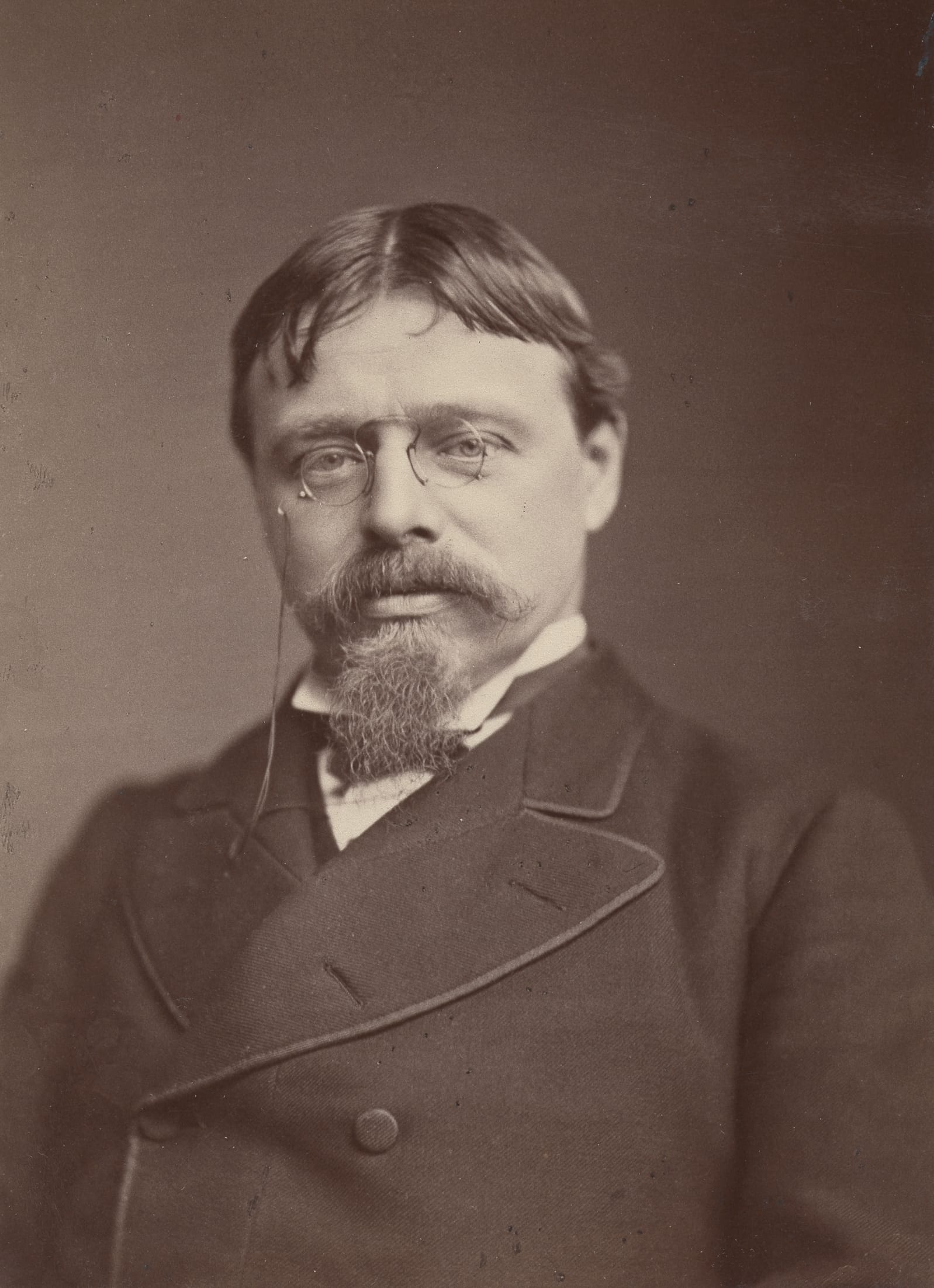

About the Artist

Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912) was a Dutch-born painter who became one of the most famous Victorian artists of classical subjects. Renowned for his meticulous research, he recreated Roman and Greek settings with archaeological precision. His works often combined dazzling beauty with subtle social commentary, making antiquity resonate with Victorian audiences. Alma-Tadema’s influence extended to 20th-century cinema, where his visions of Rome shaped epic films such as Ben-Hur and Gladiator.

The Story Behind the Painting

The Emperor Heliogabalus

Heliogabalus (also known as Elagabalus, reigned AD 218–222) was notorious in Roman history for extravagance and scandal. Ancient writers described his reign as a whirlwind of indulgence and theatrical excess.

The Banquet of Roses

According to legend, Heliogabalus arranged banquets where guests were buried under masses of flower petals. Alma-Tadema seizes this moment, portraying the emperor calmly watching as petals pour down in deadly abundance.

Victorian Fascination with Decadence

For Alma-Tadema’s contemporaries, the subject resonated with anxieties about empire, indulgence, and decline. Rome’s excess was both a source of fascination and a mirror held up to Victorian society.

Composition and Subjects

The Emperor’s Calm

Heliogabalus reclines at the head of the table, dressed in gold and purple, gazing with amusement at his suffocating guests. His detachment emphasizes the cruelty of the act.

The Banqueters

The guests, once reveling in luxury, are now overwhelmed by roses. Some raise arms to protect themselves, others sink into helplessness, their bodies half-buried in blossoms.

The Roses Themselves

Thousands of pink petals dominate the canvas, painted with such detail that they almost overflow from the frame. They symbolize beauty turned lethal, pleasure transformed into destruction.

Art Style and Techniques

Classical Realism

Alma-Tadema’s archaeological accuracy — the marble colonnade, mosaic floors, and Roman costumes — anchors the scene in historical authenticity.

A Feast of Color

The pinks of the roses dominate, contrasted against white marble and golden drapery, creating a visual saturation that mirrors the theme of excess.

Symbolism of Decadence

The roses, traditionally a symbol of love and beauty, become instruments of suffocation. Alma-Tadema transforms an emblem of delight into a metaphor of danger.

Featured in Our Collection

The Roses of Heliogabalus is included in our Neoclassicism & Victorian Spot-the-Difference Puzzle Flipbook P2. Its extraordinary details — cascades of petals, intricate robes, and expressions of guests — provide both challenge and delight for puzzle lovers. This masterpiece of spectacle and symbolism is now a puzzle that lets you explore every petal and shadow with fresh eyes.

Banquet of Roses

A sea of petals descends, guests struggle beneath the weight, and a young emperor looks on with idle calm. Alma-Tadema’s The Roses of Heliogabalus is at once dazzling and chilling — a vision of beauty turned fatal.

More About Artist

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema OM, RA (January 8, 1836 – June 25, 1912) was a Dutch-born British painter acclaimed for his detailed and lavish depictions of scenes from the ancient world. Born in Dronrijp, Netherlands, Alma-Tadema received his artistic training at the Royal Academy of Antwerp under the Belgian historical painter Hendrik Leys. In 1870, he settled in London, becoming a naturalized British subject in 1873, and rose to prominence for his meticulous and evocative paintings of Roman, Greek, and Egyptian antiquity.

Artist Style and Movement

Alma-Tadema is known for his neoclassical style, characterized by an extraordinary attention to detail, especially in his rendering of marble textures, ancient architecture, and luxurious costumes. His works often present anecdotal scenes of daily life and luxury within ancient civilizations, capturing moments with archaeological accuracy and a vivid sense of realism. He bridged academic painting with historical romanticism, becoming one of the most admired Victorian painters before his style fell out of favor early in the 20th century.

Artwork Profile

- The Education of the Children of Clovis (1861): Alma-Tadema’s breakthrough work, depicting Queen Clotilde instructing her sons in warfare in a detailed, classical courtyard setting.

- The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888): An opulent scene portraying the Roman Emperor Heliogabalus showering guests with rose petals to dangerous excess.

- An Audience at Agrippa’s (1876) and After the Audience: Companion pieces showing a Roman imperial scene with emotional subtlety.

- The Coliseum (1896) and The Baths of Caracalla (1899): Architectural masterpieces illustrating Rome’s grandeur.

- The Finding of Moses (1904): A delicate painting of Pharaoh’s daughter discovering Moses, rich in Egyptian detail.

- Numerous portraits, landscapes, and etchings complement his historic and classical subjects.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s rich body of work stands as a testament to Victorian fascination with antiquity, merging scholarly archaeological observation with romantic imagination. His meticulous craftsmanship and vivid storytelling continue to captivate viewers, establishing him as a leading figure in 19th-century classical and historicist painting. Though he experienced a decline in popularity posthumously, a resurgence of interest from the mid-20th century onward has restored his status in art history.