Table of Contents

Overview

Charon and Psyche (1883) by John Roddam Spencer Stanhope depicts a solemn mythological encounter between mortal soul and ferryman of the underworld. Psyche, robed in blue and orange, extends payment for passage across the river Styx. Charon, weathered and muscular, leans from his boat to accept her offering, oar in hand, while the shadowed waters and rocky caverns deepen the scene’s gravity.

Stanhope (1829–1908), a second-generation Pre-Raphaelite, often merged classical themes with spiritual allegory. In this work, he transforms the Greek myth into a meditation on death, transition, and the soul’s journey. His jewel-like palette, Renaissance-inspired figures, and symbolic landscape embody the ideals of Pre-Raphaelite art filtered through Florentine influence.

Exhibited in the 1880s, Charon and Psyche resonated with Victorian audiences fascinated by myth, mortality, and the afterlife. Today, it remains one of Stanhope’s most haunting allegories, uniting mythic narrative with spiritual reflection.

The Artist

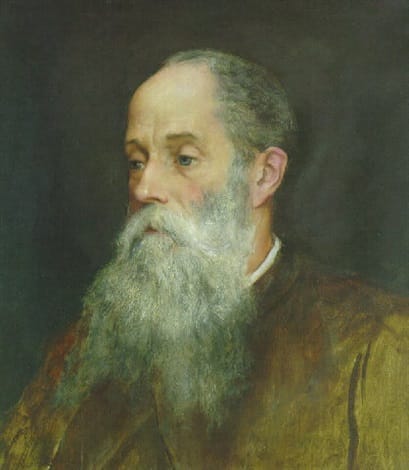

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope (1829–1908) was an English painter linked to the later Pre-Raphaelite circle. A cousin of Rossetti and close associate of Burne-Jones, he spent much of his career in Florence, where Renaissance harmony and color profoundly shaped his art. Stanhope explored themes from the Bible, classical mythology, and allegory, painting with jewel-like clarity and solemn rhythm. Though less famous than his contemporaries, his works bridge realism and symbolism with poetic resonance.

The Story Behind the Painting

The Myth of Psyche

In Greek mythology, Psyche represents the human soul. Her trials to reunite with Eros (Cupid) symbolize transformation, faith, and the immortal longing for love. One of her tasks involves descending into the underworld — an act requiring courage and payment to Charon, ferryman of the Styx.

Charon the Ferryman

Charon, a figure of inevitability, transported souls of the dead across the Styx if they bore coin for passage. Without payment, spirits wandered in limbo. Stanhope paints the exchange with solemn intensity: mortal fragility meets eternal law.

Victorian Fascination with the Afterlife

To Victorian audiences, myths of Psyche symbolized the soul’s immortality, while Charon embodied the passage from life to eternity. The painting therefore echoed not only classical legend but also spiritual meditation, aligning with the Pre-Raphaelite love for moral allegory.

Composition and Subjects

Psyche the Mortal Soul

At the left, Psyche steps barefoot into shadow, her blue robe bound with an orange sash. She extends her hand with offering, her youthful face calm yet resolute. She is innocence facing inevitability.

Charon the Ferryman

On the right, Charon leans from his boat, his muscular form draped in rough brown cloth. His beard and stern gaze embody endurance and inevitability. His oar rests at his side, ready to guide souls into shadow.

The Waters of the Styx

Dark, still, and surrounded by cavernous rock, the river Styx is rendered with eerie depth. Its greenish reflections evoke a world between life and death, a threshold that cannot be reversed.

Figures in the Shadows

At the far left, ghostly forms of souls linger, awaiting passage. Their faint presence reminds the viewer that Psyche is not alone — she represents every human soul on its eternal journey.

Art Style and Techniques

Jewel-like Clarity

Stanhope employs glowing colors — Psyche’s blue, Charon’s earthy tones, the river’s green — to heighten symbolic contrast. The figures stand luminous against the shadowed background.

Renaissance Harmony

The composition recalls Renaissance frescoes: calm, frieze-like arrangement, balanced gestures, and solemn rhythm. This influence reflects Stanhope’s years in Florence.

Pre-Raphaelite Symbolism

Every element conveys allegory: the coin as faith, Charon as inevitability, the water as transition, and Psyche as the soul’s courage. Stanhope transforms myth into timeless meditation.

Legacy and Reflection

Reception

Victorian critics admired Charon and Psyche for its solemnity and symbolic depth. It was seen as an allegory not only of myth but of humanity’s spiritual journey — a theme resonating deeply with an age preoccupied with mortality and faith.

Lasting Significance

Today, the painting is celebrated as one of Stanhope’s finest mythological works. It unites the Brotherhood’s fidelity to detail with Symbolist undertones, foreshadowing the spiritual modernism of the early 20th century.

Featured in Our Collection

Charon and Psyche is featured in our Pre-Raphaelite Spot-the-Difference Puzzle Flipbook Part 2. Its shadowed river, luminous figures, and symbolic gestures make it a captivating puzzle subject. By seeking differences hidden in Stanhope’s intricate vision, you sharpen perception while engaging with the eternal themes of myth, mortality, and the soul’s passage.

Across the Waters of the Styx

The soul extends her hand, the ferryman accepts, and the waters lie still between. In Charon and Psyche, Stanhope paints a myth not of terror but of solemn beauty — the eternal journey made visible in color, gesture, and shadow.

More About Artist

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope (January 20, 1829 – August 2, 1908) was an English artist associated with the second wave of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Born into an aristocratic family in Cawthorne, Yorkshire, he was educated at Rugby School and Christ Church, Oxford. Despite his privileged background, Stanhope pursued a career in art, training under George Frederic Watts and traveling extensively, including trips to Italy and Asia Minor.

Artist Style and Movement

Stanhope’s work is typically classified within the later Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic movements of Victorian art. He worked across various media—oil, watercolor, fresco, tempera—and his subjects ranged from mythological and allegorical themes to biblical scenes and contemporary life. His early paintings featured highly original narrative compositions, which later evolved towards a more symbolic and aesthetic style influenced by broader Victorian artistic trends.

The Pre-Raphaelite Society continues to explore and share the legacy of this remarkable movement.

Artwork Profile

- Thoughts of the Past (1859), his first exhibited painting, depicting a contemplative woman by a window overlooking the Thames.

- The Shulamite: (Pastoral Scene with Lambs) (c. 1878), a serene and lyrical pastoral scene exemplifying his Pre-Raphaelite style.

- The Shulamite: (Bridal Procession) (c. 1882), depicting the procession with rich symbolism and ornate detail, continuing his Pre-Raphaelite themes.

- Penelope (1864), illustrating the faithful wife from Homeric legend in the detailed and expressive Pre-Raphaelite manner.

- Winnowing (c. 1880), portraying agricultural life with symbolic overtones typical of his narrative approach.

- Juliet and Her Nurse (c. 1860), a literary subject rich with emotional and dramatic qualities favored by Pre-Raphaelites.

- Why Seek ye the Living Among the Dead (1870–1899), a powerful biblical scene reflecting later symbolic and aesthetic tendencies.

- Love and the Maiden (1877), a romantic and allegorical composition showcasing his mature style.

- Charon and Psyche (1883), a mythological painting exploring themes of love and the afterlife.

- Pine Woods at Viareggio (1888), a landscape reflecting his time in Italy with delicate naturalism.

- The Gentle Music of a Bygone Day (1873), a nostalgic genre painting evoking memories and emotion.

- The Waters of Lethe by the Plains of Elysium (1880), a symbolic work referencing classical mythology and the afterlife.

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope’s artistic career reflects a rich engagement with the ideals of the Pre-Raphaelites, combined with a move towards aesthetic symbolism in later years. His work, characterized by technical skill and narrative depth, secured him a distinctive place in Victorian art history. Living much of his later life in Florence, he influenced subsequent artists including his niece Evelyn De Morgan, solidifying his legacy as a key figure bridging English Romanticism and Aestheticism.phasize classical virtue and patriotic sacrifice, reflecting the cultural ideals of his age.