Table of Contents

Overview

Dante and Beatrice (1883) by Henry Holiday captures a pivotal moment in literary and artistic history. Inspired by Dante Alighieri’s La Vita Nuova, the painting shows the poet encountering Beatrice Portinari, the woman who became his muse and eternal symbol of divine love.

Set against the golden light of Florence, Holiday presents not just a meeting of two people but the birth of a vision that would shape poetry for centuries. In jewel-like colors and exacting detail, he unites Pre-Raphaelite naturalism with Renaissance atmosphere, creating an image that is both intimate and monumental.

The Story Behind the Painting

Dante’s Inspiration

Dante first saw Beatrice as a young boy in Florence and later wove her into his poetry as the embodiment of purity and divine grace. In La Vita Nuova (The New Life), he recounts encounters with her, mingling autobiography with allegory. Beatrice appears again in The Divine Comedy, guiding Dante through Paradise as a symbol of divine wisdom.

Holiday chooses the moment of their encounter on the streets of Florence — an ordinary event transformed into eternal myth.

Henry Holiday and the Pre-Raphaelite Circle

Henry Holiday (1839–1927) was part of the later Pre-Raphaelite movement, known for his painting, stained glass, and illustration. Deeply influenced by John Ruskin and Burne-Jones, Holiday embraced the Brotherhood’s ideals of truth to nature, literary inspiration, and meticulous detail. Dante and Beatrice reflects both Pre-Raphaelite devotion to narrative and the late-Victorian fascination with medieval Italy.

A Victorian Renaissance

To Victorian audiences, Dante’s love for Beatrice represented not only romantic devotion but also moral and spiritual elevation. By painting this meeting, Holiday aligned Dante’s vision with the Pre-Raphaelite project: the union of art, literature, and faith into a single, elevated aesthetic.

Composition and Subjects

The Florence Setting

The scene unfolds along the Lungarno, with Florence’s bridges and ochre rooftops glowing in the distance. The Arno river reflects soft light, and pigeons scatter across the cobblestones — natural touches that anchor the allegory in daily life.

Beatrice and Her Companions

At the center, Beatrice walks with two companions, their gowns flowing in rich colors: crimson, gold, and sapphire blue. Beatrice herself wears golden yellow, holding a flower as a quiet emblem of beauty and grace. Her gaze is steady, her posture dignified, as if aware of the destiny her presence carries.

Dante’s Encounter

On the right, Dante stands apart, cloaked in deep green with a red cap, one hand resting on the balustrade, the other over his heart. His expression is intent yet restrained, a mixture of reverence and longing. The gulf of space between him and Beatrice heightens the drama — a physical separation that mirrors the emotional and spiritual distance of their love.

Symbolic Details

Every detail carries meaning. Beatrice’s golden gown glows as though lit from within, echoing her role as a figure of divine light. The pigeons, symbols of fidelity and peace, scatter but remain close, reminding us of love’s fragility. The placement of Dante and Beatrice at opposite ends of the composition emphasizes their separation, even within the same frame.

Art Style and Techniques

Jewel-like Pre-Raphaelite Color

Holiday employs the Pre-Raphaelite palette with precision — vivid reds, glowing yellows, and rich blues that shimmer against the sunlit backdrop. The colors are clear and unblended, creating a crystalline effect that gives the scene a timeless clarity.

Attention to Natural Detail

From the cobblestones beneath the figures’ feet to the pigeons in flight and the distant architecture, Holiday renders every detail with scientific observation. This “truth to nature” reflects John Ruskin’s influence and the Brotherhood’s founding ideals.

Renaissance Echoes

The composition is deeply influenced by Italian Renaissance art. The frieze-like arrangement of figures, the dignified poses, and the architectural setting evoke frescoes of Florence. Holiday bridges centuries: Dante’s medieval Florence becomes a Victorian dream of the Renaissance.

Legacy and Reflection

Reception and Importance

Exhibited in 1883, Dante and Beatrice was admired for its beauty and historical resonance. It reinforced Victorian fascination with Dante, whose works were widely translated and celebrated in the 19th century.

The Eternal Symbol

To Dante, Beatrice became more than a woman — she was the guide to truth and divine wisdom. Holiday’s painting captures both the earthly encounter and its eternal significance, freezing in time the moment where love, poetry, and destiny converge.

On the streets of Florence, amid pigeons and golden light, Dante looks toward Beatrice — a fleeting glimpse that became an eternal vision. In Holiday’s hands, their meeting is not just history but myth: love as poetry, poetry as devotion, devotion as art.

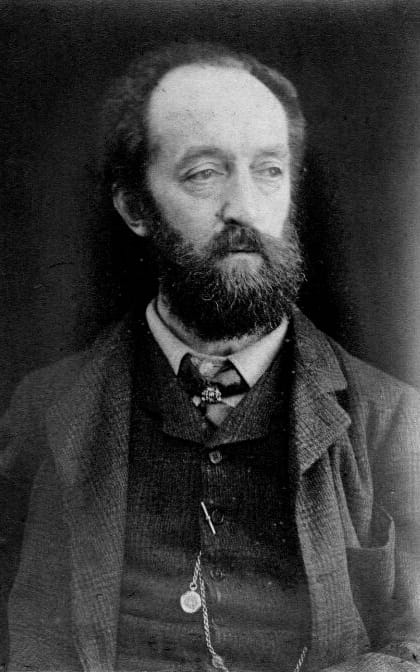

About Artist

Henry Holiday (June 17, 1839 – April 15, 1927) was an English Victorian painter known for his historical genre scenes, landscapes, stained-glass designs, and illustrations. Born in London, Holiday was trained as a painter and later gained renown for his dual talents as a visual artist and designer. He was deeply influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite movement and contributed significantly to its development during the late 19th century.

Artist Style and Movement

Holiday’s artistic style is rooted in the Pre-Raphaelite tradition, blending vivid detail, rich color, and literary and historical themes. Beyond easel painting, he was an influential stained-glass designer and book illustrator. His style emphasized accuracy, symbolism, and narrative depth. His works often reflected medieval, Renaissance, and mythological subjects, with an academic yet highly decorative approach.

Notable Works

- Dante and Beatrice (1883): Holiday’s most celebrated painting, housed in the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, depicts a scene from Dante Alighieri’s La Vita Nuova. It shows Beatrice refusing Dante’s greeting as they pass near the Santa Trinita Bridge in Florence. Holiday was meticulous in historical accuracy, studying 13th-century Florence architecture and costumes to render the scene authentically.

- The Rhine Maiden (1879): A mythological work inspired by Wagnerian opera themes, showcasing Holiday’s interest in literary and allegorical subjects.

- The Fairy Wood (1867): A lush, imaginative genre scene celebrating folklore and fairy tales.

- Work and Wages (ministering themes of Victorian social conscience)

- Stained-glass windows for prominent institutions like Westminster Abbey and various churches, reinforcing Holiday’s impact beyond painting.

The Last Pre-Raphaelite

Henry Holiday was often described as “the last Pre-Raphaelite” due to his enduring commitment to the movement’s principles even as Victorian art evolved. He maintained the Pre-Raphaelite ideals of detailed realism, complex symbolism, and romantic historicism late into his career when many contemporaries had moved on to other styles. His preservation of the movement’s aesthetic and narrative finesse cemented his title as a key figure bridging the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with later 19th-century British art.

Holiday’s career spanned multiple artistic disciplines, embodying the Pre-Raphaelite dedication to craftsmanship, storytelling, and historical accuracy. His masterpiece Dante and Beatrice remains a hallmark of Victorian art, combining emotional depth with scholarly precision. Celebrated as the last true Pre-Raphaelite, Holiday contributed richly to the legacy of 19th-century British art, influencing stained glass, illustration, and painting alike.