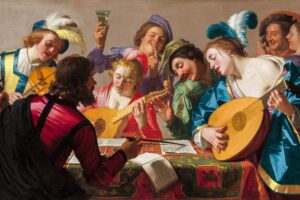

The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons

Jacques-Louis David, 1789

A Moment of Heartbreak and Resolve

Painted on the eve of the French Revolution, Jacques-Louis David’s The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons captures one of the most tragic and heroic moments in Roman history. It’s a story about justice, sacrifice, and the painful cost of staying true to one’s principles—even when it means turning against your own family.

In this solemn scene, Lucius Junius Brutus sits in deep shadow. He has sentenced his two sons to death for plotting to restore the monarchy he helped overthrow. The lictors—Roman guards—now return with their lifeless bodies.

But David paints more than a verdict. He gives us a full stage of human sorrow and moral strength.

A Father’s Silence

Brutus sits motionless at the far left, cloaked in heavy thought. His posture is firm, his feet bare, and one hand grips the bench beneath him—a silent storm of pain. His face turns away from the figures entering, away from the bodies of his sons, away even from his grieving family. He has chosen duty to the republic over the love of a father, and now bears the weight of that decision.

A single bundle of shears lies at his feet—a reminder of the law’s cutting force.

The Women Left Behind

On the right side of the painting, where the light falls more fully, we see four women, each showing a different kind of grief:

- The Mother, tall and regal in a cream-colored robe, bends forward in shock. She clutches her hands, her whole body arching with disbelief and sorrow. She has just glimpsed her sons being returned lifeless, and the heartbreak rises in her eyes.

- The Older Sister, dressed in soft pink, collapses in anguish. Her body droops backward as if her spirit has left her—either fainting or frozen in grief. Her head leans toward her mother, seeking comfort that cannot be found.

- The Younger Sister, smaller and closer to the front, clasps her sister in despair. Her wide, tear-filled eyes are fixed on the lictors, the horror of the moment fresh in her young heart.

- The Maidservant, standing slightly behind, covers her face with her robe. She cannot bear to look. Her gesture shields her from the cruelty of justice and the collapse of a family she served.

Together, these women form a powerful counterweight to Brutus’s stoic form. Where he embodies the sacrifice of duty, they express the full weight of loss.

Painted for a New Age

David completed this painting in 1789, as France stood on the brink of revolution. By telling this Roman tale, he offered a message to his fellow citizens: liberty has a cost, and justice must be equal, even when it cuts close to home.

The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons is not just a history painting—it’s a moral compass, a political voice, and a timeless portrait of the strength it takes to stand by one’s values.

A Legacy Etched in Silence

In the shadows, Brutus does not cry. He does not move. But we feel everything he cannot say.

And in the light, the cries of the women echo through time. David shows us the cost of founding a republic—not in blood alone, but in broken hearts.

About Artist

Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) was a French painter who became the leading figure of Neoclassicism, a movement that rejected the frivolity of the Rococo and sought to revive the moral and aesthetic values of ancient Greece and Rome. His art was not just beautiful; it was a powerful tool for political and social change. David’s work defined a new style that was severe, intellectual, and deeply political, making him a central figure in the French Revolution and later, the court of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Artistic Style and Legacy

David’s style is characterized by a dramatic shift from the soft, sensual curves of Rococo to the sharp lines and moral clarity of Neoclassicism. His paintings are known for:

- Classical Themes and Heroes: He drew heavily from ancient history and mythology to tell stories of virtue, civic duty, and self-sacrifice.

- Sharp, Defined Lines: He rejected the loose brushwork of the Rococo in favor of crisp, sculptural forms that give his figures a sense of heroic grandeur.

- Moral and Political Messages: His art often served as propaganda, urging viewers to embrace patriotism and civic virtue.

- Controlled Lighting: He used strong, raking light to emphasize form and clarity, avoiding the dramatic tenebrism of the Baroque.

Artwork Profile

Here paintings represent the full range of his career, from his early Neoclassical masterpieces to his later works for Napoleon.

- Belisarius Begging for Alms (1781): An early Neoclassical work that depicts the Roman general Belisarius, unjustly fallen into disgrace, begging for money. It’s a clear moral statement about the cruelty of the state.

- The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons (1789): A powerful and stark depiction of a Roman leader who chose civic duty over personal love. This painting, with its clear composition and somber tone, was seen as a call for revolutionary sacrifice.

- The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis (1782): A more sentimental and intimate work from his early career, it depicts a scene from a classical novel, showing his softer side before his full turn to political subjects.

- The Death of Socrates (1787): One of his most famous masterpieces. It portrays the Greek philosopher Socrates as a moral hero calmly facing death. The painting’s noble composition and stoic emotion made it an icon of Enlightenment ideals.

- The Anger of Achilles (1819): This late painting, from his exile in Brussels, shows David returning to classical subjects with a more refined and emotionally charged style.

- Oath of the Horatii (1784): Arguably his most famous work and a manifesto of Neoclassicism. It depicts three Roman brothers swearing an oath to their father, prioritizing duty to Rome over family. Its stark, geometric composition and powerful moral theme made it an instant sensation.

- Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801): A famous equestrian portrait of Napoleon as a heroic figure. The painting is a work of political propaganda, portraying Napoleon as a dynamic and determined leader.

- The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries (1812): A more intimate portrait of Napoleon, but one that still emphasizes his power and intellectual prowess. It shows the emperor standing in his study late at night, a subtle nod to his tireless work ethic.

This Painting, The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons, is Featured in (Neoclassicism Spot the Difference Puzzles : Interactive, Printable Flipbook) by Classic Art Puzzles.