The Calling of Saint Matthew – Caravaggio, 1599–1600

In a dim tavern corner, amid coins, ledgers, and shadows, a moment unfolds that will change a life—and echo across centuries. The Calling of Saint Matthew is one of Caravaggio’s most profound masterpieces, where sacred intervention slips quietly into the ordinary world.

Here, the divine does not thunder. It points.

The Scene Before Us

Five men huddle at a table, counting silver, dressed in fine Renaissance garments. The scene is earthy, familiar—until two figures enter from the right. One of them is Christ. Barefoot, cloaked in shadow, his arm extends toward the group. His hand, reminiscent of Adam’s in Michelangelo’s Creation, reaches not for grandeur—but for a tax collector.

A sliver of light cuts through the darkness and lands on Matthew’s face. His finger lifts in disbelief, as if to say, “Me?” His eyes widen. His companions remain distracted. Time seems to slow, breath suspended.

Caravaggio, master of chiaroscuro, paints this moment with sharp contrast—light as revelation, darkness as denial, the tension between grace and habit.

The Deeper Meaning

This is not a miracle painted in marble. It is grace arriving in the midst of business, in the middle of counting coins. Christ comes not with trumpets, but in the company of Peter, stepping quietly into a world preoccupied with itself.

Matthew, though stunned, is already changing. His gesture—half-question, half-recognition—tells us everything. He doesn’t rise yet. He doesn’t speak. But the light has found him. And that, Caravaggio suggests, is where the transformation begins.

The other men at the table remain in shadow—absorbed in wealth, in habit, in the safety of known things. They do not see what Matthew sees.

Caravaggio knew this tension well. He lived it: a man torn between darkness and illumination, brawls and beauty, sacred commissions and scandal. That’s why this painting feels so lived-in—because its moment is real. Not lofty, but reachable.

A Moment Caught in Time

This is not a painting of sainthood. It is a painting of beginning. Of the exact moment when a man becomes more than he was a second before—not through his own action, but by being seen. And in that pause, between silver and spirit, he begins to rise.

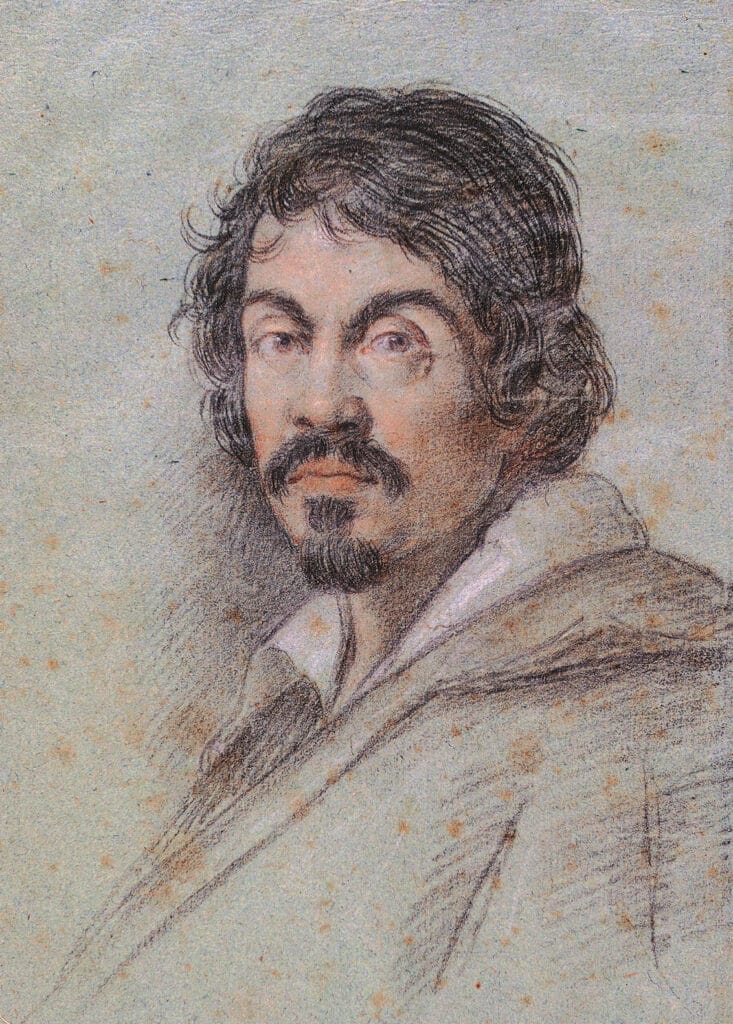

About Artist

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) was an Italian painter who single-handedly revolutionized painting and became a pivotal figure of the Baroque art movement. Living a tumultuous and often violent life, he created a body of work that was both intensely realistic and profoundly dramatic. His radical approach broke away from the idealized forms of the Renaissance and Mannerism, influencing a generation of artists known as the Caravaggisti.

Artistic Innovations

Caravaggio’s genius lies in his revolutionary use of a technique now known as tenebrism. This is an extreme form of chiaroscuro that uses a dramatic, single light source to create stark contrasts between light and dark, plunging the background into deep shadow while illuminating the figures in a theatrical spotlight. This technique heightens the emotional intensity of his scenes.

He also shocked his contemporaries with his radical naturalism. Unlike artists who used idealized models, Caravaggio often painted directly from life, using real people—including beggars, laborers, and prostitutes—as models for his saints and biblical figures. This brought a new, raw, and often shocking level of humanity to religious subjects. His paintings feel immediate and tangible, as if the sacred events are unfolding in a contemporary, ordinary setting.

Notable Works

- “The Calling of Saint Matthew” (1599–1600): This masterpiece, housed in the Contarelli Chapel in Rome, is a perfect example of his style. A single ray of light from an unseen source illuminates the tax collectors in a dark room as Christ, on the right, calls Matthew to follow him. The scene feels less like a historical event and more like a pivotal, everyday moment.

- “Basket of Fruit” (c. 1599): A truly groundbreaking painting, this is one of the earliest examples of a stand-alone still life in Italian art. Rather than depicting perfect, idealized fruit, Caravaggio rendered the basket’s contents with unflinching realism, including wormholes in an apple and a shriveled leaf. This work is often interpreted as a “memento mori,” a reminder of the transience of life and the inevitability of decay.

- “Judith Beheading Holofernes” (c. 1599): This intensely violent and psychological painting depicts the biblical heroine Judith in the act of beheading the Assyrian general. The scene is full of drama and emotion, with Judith’s face conveying a mixture of determination and revulsion.

- “The Supper at Emmaus” (1601): This work captures the moment the disciples recognize the resurrected Christ. The gestures are explosive, with one disciple’s arms outstretched in shock. The illusion of a meal on the table, with a basket of fruit seemingly about to topple off, brings the divine event into the viewer’s immediate space.

- “The Entombment of Christ” (1602–1603): Considered one of his greatest masterpieces, this painting focuses on the raw grief of those lowering Christ’s body into the tomb. The light, the weight of the bodies, and the powerful expressions of sorrow create a moving and unforgettable devotional image.