The Fortune Teller – Caravaggio, c. 1595

A young man stands confidently, his hand extended to a woman who claims to read fate. He believes himself clever—perhaps even flirtatious—but Caravaggio sees deeper. In The Fortune Teller, painted around 1595, the young master of chiaroscuro captures a timeless moment of charm, deceit, and the delicate tension between appearance and truth.

This is no grand myth or sacred vision. It is something closer: a scene of everyday humanity, dressed in velvet and caution.

The Scene Before Us

A handsome youth, finely dressed in embroidered gold and soft black, looks down at a woman in simple but dignified garments. His body is poised with casual confidence, his hand resting on his hip, a sword at his side. He smiles, amused, as she gently takes his hand in hers.

The woman’s expression is calm, almost tender. Her white turban and modest dress suggest humility—but her eyes gleam with quiet cunning. As she reads his palm, her fingers slide along his, lightly lifting the ring from his finger. The act is so subtle, so precise, that even he, though watching her intently, does not notice.

Caravaggio’s light carves the scene with clarity—illuminating skin, fabric, and gesture—while the background fades into warm, unspoken shadow. The contrast between brightness and obscurity echoes the moral tension at play.

The Deeper Meaning

Caravaggio was fascinated by truth—how it hides, how it pretends. The Fortune Teller is not just about thievery; it’s about confidence, in every sense of the word. The young man exudes confidence in himself, in his judgment, in his charm. But confidence also invites overreach. His pride blinds him.

The woman, often miscast as a mere thief, is not presented cruelly. She is clever, composed, and entirely in control. She is part illusionist, part realist—making the invisible visible to him while concealing her own sleight of hand.

This is not just a con—it is a dance. A moment when deception masquerades as intimacy, when touch disguises transaction.

Caravaggio leaves us to wonder: is he a fool, or is he willingly enchanted? And how often do we ourselves play both roles?

A Moment Caught in Time

The painting freezes the instant before revelation—the ring not yet gone, the truth not yet noticed. That brief heartbeat of trust, when the world still feels in your favor.

Caravaggio, only in his mid-twenties when he painted this, already understood what so many older artists missed: that drama lives not in heroes or battles, but in quiet, everyday betrayals—and in the expressions that betray us long before our pockets do.

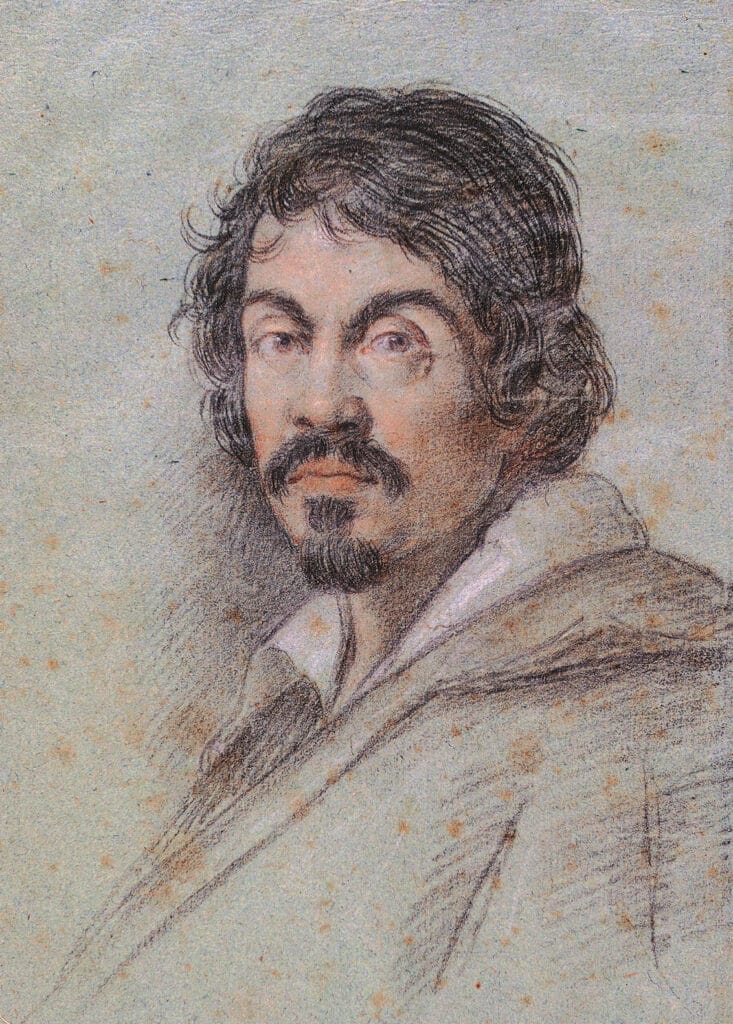

About Artist

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) was an Italian painter who single-handedly revolutionized painting and became a pivotal figure of the Baroque art movement. Living a tumultuous and often violent life, he created a body of work that was both intensely realistic and profoundly dramatic. His radical approach broke away from the idealized forms of the Renaissance and Mannerism, influencing a generation of artists known as the Caravaggisti.

Artistic Innovations

Caravaggio’s genius lies in his revolutionary use of a technique now known as tenebrism. This is an extreme form of chiaroscuro that uses a dramatic, single light source to create stark contrasts between light and dark, plunging the background into deep shadow while illuminating the figures in a theatrical spotlight. This technique heightens the emotional intensity of his scenes.

He also shocked his contemporaries with his radical naturalism. Unlike artists who used idealized models, Caravaggio often painted directly from life, using real people—including beggars, laborers, and prostitutes—as models for his saints and biblical figures. This brought a new, raw, and often shocking level of humanity to religious subjects. His paintings feel immediate and tangible, as if the sacred events are unfolding in a contemporary, ordinary setting.

Notable Works

- “The Calling of Saint Matthew” (1599–1600): This masterpiece, housed in the Contarelli Chapel in Rome, is a perfect example of his style. A single ray of light from an unseen source illuminates the tax collectors in a dark room as Christ, on the right, calls Matthew to follow him. The scene feels less like a historical event and more like a pivotal, everyday moment.

- “Basket of Fruit” (c. 1599): A truly groundbreaking painting, this is one of the earliest examples of a stand-alone still life in Italian art. Rather than depicting perfect, idealized fruit, Caravaggio rendered the basket’s contents with unflinching realism, including wormholes in an apple and a shriveled leaf. This work is often interpreted as a “memento mori,” a reminder of the transience of life and the inevitability of decay.

- “Judith Beheading Holofernes” (c. 1599): This intensely violent and psychological painting depicts the biblical heroine Judith in the act of beheading the Assyrian general. The scene is full of drama and emotion, with Judith’s face conveying a mixture of determination and revulsion.

- “The Supper at Emmaus” (1601): This work captures the moment the disciples recognize the resurrected Christ. The gestures are explosive, with one disciple’s arms outstretched in shock. The illusion of a meal on the table, with a basket of fruit seemingly about to topple off, brings the divine event into the viewer’s immediate space.

- “The Entombment of Christ” (1602–1603): Considered one of his greatest masterpieces, this painting focuses on the raw grief of those lowering Christ’s body into the tomb. The light, the weight of the bodies, and the powerful expressions of sorrow create a moving and unforgettable devotional image.