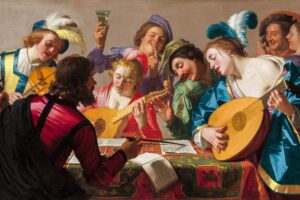

The Marriage Feast at Cana – Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, c. 1672

The table is long, the garments fine, the celebration in full swing. Yet something deeper stirs beneath the joy and ceremony—something sacred, something quietly miraculous. In The Marriage Feast at Cana, Murillo, the Spanish master of light and tenderness, captures a moment where the divine moves among the ordinary, unnoticed by most but transformative for all.

The Scene Before Us

We are drawn into a grand wedding banquet. The table overflows with fruit, bread, pastries, and fine vessels. Guests gather close, their faces a mix of delight and curiosity. At the center, a newlywed bride glows under her floral crown, surrounded by guests, musicians, and household servants.

Christ sits calmly to one side—barefoot, humble, nearly lost in the crowd. Yet his gesture is unmistakable: a quiet command, a turning point. Next to him, Mary watches, her expression one of gentle urgency. At her request, he has agreed to act—not with spectacle, but with a gesture only a few will notice.

At the foreground, large jugs are being filled. A servant pours water while a child watches, unaware that in a breath’s time, the water will become wine.

The Deeper Meaning

Murillo paints not just a wedding, but a transformation. And he does so with a grace that feels almost casual. The miracle isn’t center stage—it’s at the edge, like a whisper in the midst of music. That is what makes it feel true.

The figures, though robed in 17th-century Spanish fashion, carry timeless expressions. Their joy, distraction, service, and awe belong to all ages. Some are too busy serving to notice the divine in their midst. Others laugh, toast, and eat. A few watch quietly, sensing something more.

This is not only about water turned to wine—it is about how the divine chooses to arrive: gently, humbly, through the rhythms of human life.

A Moment Caught in Time

Murillo does not dramatize the miracle—he softens it, lets it flow through hands and vessels, through glances and gestures. What matters is not spectacle, but presence. Christ is here, in this moment of joy, in this need for help, in this intimate act of grace.

And so the painting speaks to all who have ever hoped for quiet intervention—for the sacred to meet the simple, for help to arrive without announcement, for joy to be preserved when it seemed it might run dry.

About Artist

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682) was one of the most celebrated and influential painters of the Spanish Baroque period. While contemporaries like Zurbarán were known for their stark realism and intense piety, Murillo developed a softer, more idealized style that earned him immense popularity, particularly for his tender religious paintings and charming depictions of street life in Seville.

Artistic Style

Murillo’s style is characterized by a “vaporoso” (vaporous or hazy) quality, which is created by his soft, diffused light and gentle brushstrokes. This technique gives his religious figures, particularly the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child, an ethereal and serene quality. His work is also known for its sentimentality and emotional accessibility, making it highly appealing to the public and perfectly suited to the Counter-Reformation ideals of the time.

Unlike many of his Spanish contemporaries, Murillo also excelled in a wide range of subjects. He painted portraits, allegorical scenes, and, most famously, genre scenes of ordinary people, especially children, whom he depicted with an unprecedented sense of dignity and innocence.

Notable Works

Murillo’s extensive body of work includes hundreds of religious paintings and a significant number of genre scenes.

- “The Young Beggar” (c. 1650): This poignant genre painting, now in the Louvre, shows a young boy picking lice from his shirt in a stark, simple setting. The work is a masterful blend of naturalism and empathy, elevating a humble subject to the level of high art.

- “The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables” (1678): This is one of Murillo’s most famous and beloved religious works. It depicts the Virgin Mary ascending to heaven on a crescent moon, surrounded by a multitude of cherubic angels. This painting became the standard visual representation for the Immaculate Conception for centuries.

- “The Marriage Feast at Cana” (c. 1672): This painting is a testament to Murillo’s ability to combine a religious miracle with a contemporary, human setting. The work depicts Christ’s first miracle, turning water into wine, but Murillo stages the scene as if it were taking place in 17th-century Seville. The figures—including a boy, possibly enslaved, in a rich red tunic—are drawn from everyday life, adding a sense of immediate reality to the divine event. The lavish details of the feast, from the fine silks to the glittering tableware, demonstrate the wealth of the merchant who commissioned the piece.